In 1968, Roberto Pignataro published his first artistic book entitled ‘A Través de Estampas’ (Through Stamps). In this book, he introduced the concept of abstract storytelling—an intriguing artistic proposition presenting readers with a series of abstract images (or stamps) while omitting any form of verbal context or supporting narratives.

This article takes a comprehensive look at the origins of Pignataro's abstract storytelling, the historical backdrop in which this book was conceived, and the creative process behind its production.

•••

Introduction

Abstract storytelling is a concept Pignataro had been cultivating since his art school years. It entails presenting a collection of visually cohesive abstractions in a sequential arrangement, with the aim of introducing a narrative dimension to the viewer’s experience.

The painting below stands as an early example of this. Created in 1958 as part of a "visual fundamentals" art class, it was initially conceived as a straightforward exercise in light and color theory. However, Pignataro employed a panel-based layout, animated motifs, and mood-shifting environments, effectively emulating the dynamics of popular sequential art forms, such as comic strips and animated films.

1958. Study on light and color by Roberto Pignataro

This approach introduced the illusion of an unfolding event, albeit in abstract form, challenging the viewer to decipher the underlying narrative while engaging in a game of creative interpretation.

Further examples of abstract storytelling can be found across various stages of his art school period. For instance, the four paintings below were part of a 1960 series, comprising nine oriental-inspired, gestural abstractions.

Although each of these pieces posses its own distinct personality and can confidently stand alone, when observed together a larger theme comes to light, coalescing from the shared artistic attributes of the paintings and finding narrative development in the interplays of their individual motifs.

As these examples demonstrate, Pignataro’s abstract storytelling works by deploying a series of visual occurrences across an implied timeline. However, abstract storytelling never commits to a specific narrative or reveals where it’s headed; it merely suggests what it feels like, hinting at behaviors, actions and moods, but ultimately letting the viewer be the sole ascriber of meaning and direction to what’s unfolding before them.

In essence, abstract storytelling encapsulates the type of experience he wanted his art to project—one that regards the viewer not as a passive observer but as a vital co-authoring partner in the artistic proposition.

The pivotal moment for Roberto Pignataro’s abstract storytelling occurred in 1968 when he decided to crystallize the concept in the form of a book, which he titled 'A Través de Estampas' (Through Stamps).

•••

Historical Context

The idea of publishing an artistic book had long appealed to Roberto Pignataro, not only because of the novel creative challenge it represented; a book would also be a great vehicle for promoting his art, allowing him to reach beyond the limits of gallery-based exhibitions, especially with international audiences.

However, these were not his only incentives. To fully understand the full range of motivations behind this idea, it is important to consider the artistic milieu in which it was conceived.

A defining characteristic of Argentina’s 1960s art scene was the proliferation of verbal rhetoric surrounding visual arts events, particularly within the avant-garde. Artists increasingly turned to essays, lectures, manifestos, prefaces, public statements, street posters, and media appearances to articulate their artistic and political views, thereby amplifying the anti-establishment sentiment that often defined their shows.

1961. “Arte Destructivo” by Kenneth Kemble. Article on the idea of destructive art

1963. Alberto Greco. Manifesto “Vivo-Dito”

1966. Brochure for “Acerca de Happenings” (“About Happenings”), series of lectures and happenings organized by Oscar Masotta at the Instituto DI Tella.

Book compiling the writings of the Argentinean Avant-Garde in the 1960s

Book compiling prologues from art shows between 1960-1981

Pignataro viewed this trend with great skepticism. As we established earlier, his artistic philosophy was rooted in the conviction that visual art was most impactful when crafted to evoke meaning from the viewer, rather than as a vehicle to deliver meaning to them.

He believed the avant-garde was engaging in the latter; by building verbal frameworks around their art (typically on matters of art, politics, and society) they were shaping an environment in which, when the viewer pondered the meaning of the artistic proposition before them, answers were already prescribed.

This is not to imply that Pignataro disagreed with the avant-garde on any matters. Rather, he believed their blending of verbal rhetoric with visual art diluted the purity of the artistic experience. In his view, the use of rhetoric was not only redundant—their perspectives were already conveyed through their artistic works, often brilliantly—but it also interfered with the viewer’s ability to engage with the art independently.

Roberto Pignataro’s ‘A Través de Estampas’ was, in no small measure, an artistic counter-response to this phenomenon; a book offering the viewer a wordless sanctuary to explore abstraction completely in their own terms, free from prefabricated context and verbal distractions, and where the only narratives would be those emerging from the viewer’s genuine reaction to the artwork.

•••

Realizing the Book

1969. A copy of ‘A Través de Estampas’ (bottom right corner) displayed at “Librería El Ateneo”, a traditional bookstore in downtown Buenos Aires.

The idea of ‘A Través de Estampas’ started to take shape in the early months of 1968. The book was envisioned to unfold as a visual journey through 30 seemingly individual abstractions, with the prospect of a larger narrative emerging with every turn of the page—as outlined by Roberto Pignataro’s principles of abstract storytelling.

While the book design process unfolded smoothly, the intricacies of the production and distribution proved to be decisive factors, shaping not only the fate of the book but also its historical significance.

In the following sections, I will chronicle Pignataro’s journey through the realization of this endeavor.

The Decision to Self-Publish

When faced with the prospect of the actual production of the book, Roberto Pignataro considered two options: secure a well-established publishing house or pursue a self-publishing approach. After weighing pros and cons, he opted for the latter—a decision that came with some caveats but ultimately reflected his commitment to artistic independence.

Circa 1964. Roberto Pignataro in his office at the Argentine Central Bank.

It's worth noting that, while Pignataro wasn't a wealthy a man, his position at the Argentine Central Bank did provide him with the means to finance his artistic career.

In the context of producing ‘A Través de Estampas’, having this financial independence proved to be both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it allowed him to enjoy full creative freedom without being subjected to editorial bias, censorship (a standard practice in Argentina at the time) or imposed deadlines.

On the other hand, by becoming a one-man operation, he forfeited access to the mighty resources of mainstream publishers, including top-tier manufacturing, advertising power and streamlined distribution networks, having to absorb much of the heavy lifting himself.

Regardless of any pros and cons, I believe what ultimately drove him towards self-publishing was the awesome realization that he could do so. It’s hard to overstate how unprecedented this was for an average middle-class Argentinean before the 1960s—to be able to independently afford the production of a book, print 500 copies, secure commercial distribution, and utilize modern airmail shipping and communications networks to achieve global exposure.

This was only made possible by the rapid technological and societal advancements of this decade, and it must have been absolutely exhilarating for any independent-minded artists like Pignataro to realize that these modern circumstances suddenly enabled them to operate without the historical constraints of art patronage and enjoy unprecedented reach and control over their artistic endeavors.

The Master Artwork

When considering the master artwork, the book format played a key role in the decision-making process. The imagery had to fit comfortably within standard page dimensions while also allowing for ample white space to ensure a clean backdrop and proper visual balance—all without feeling “scaled-down”.

Pignataro's collection of 'small-format abstractions' (1) was ideally suited for this purpose. These art pieces, often handheld in size or smaller, were carefully crafted to thrive in intimate, miniature settings, where their intricate details and subtle compositions could be appreciated up close. This made them a perfect fit for the dimensional requirements of the book.

For visual context, below I include few slides from Pignataro’s 1962 exhibition at Galería J. Peuser, where he first introduced the concept of small-format abstractions.

Print & Assembly

Although the aged slides above might not convey this accurately, color played a crucial role in small-format abstractions, adding vibrancy and emotional counterbalance to an artistic proposition that otherwise tended to submerge deep into complex psychological themes.

However, due to the expensive costs of traditional four-color printing, Pignataro opted to publish ‘A Través de Estampas’ in black and white. This decision challenged him to recalibrate some of his creative processes.

Letter to Joseph James Akston, Director of Arts Magazine (Aug 5th, 1970)

This is documented in a 1970 letter to Joseph James Akston, then Director of Arts Magazine, where Pignataro explains how his color choices for the master artwork had to be carefully curated, not to evoke specific moods or emotions, but based on his best predictions for how they would translate his artistic vision into the grayscale space of halftone printing (fifth paragraph.)

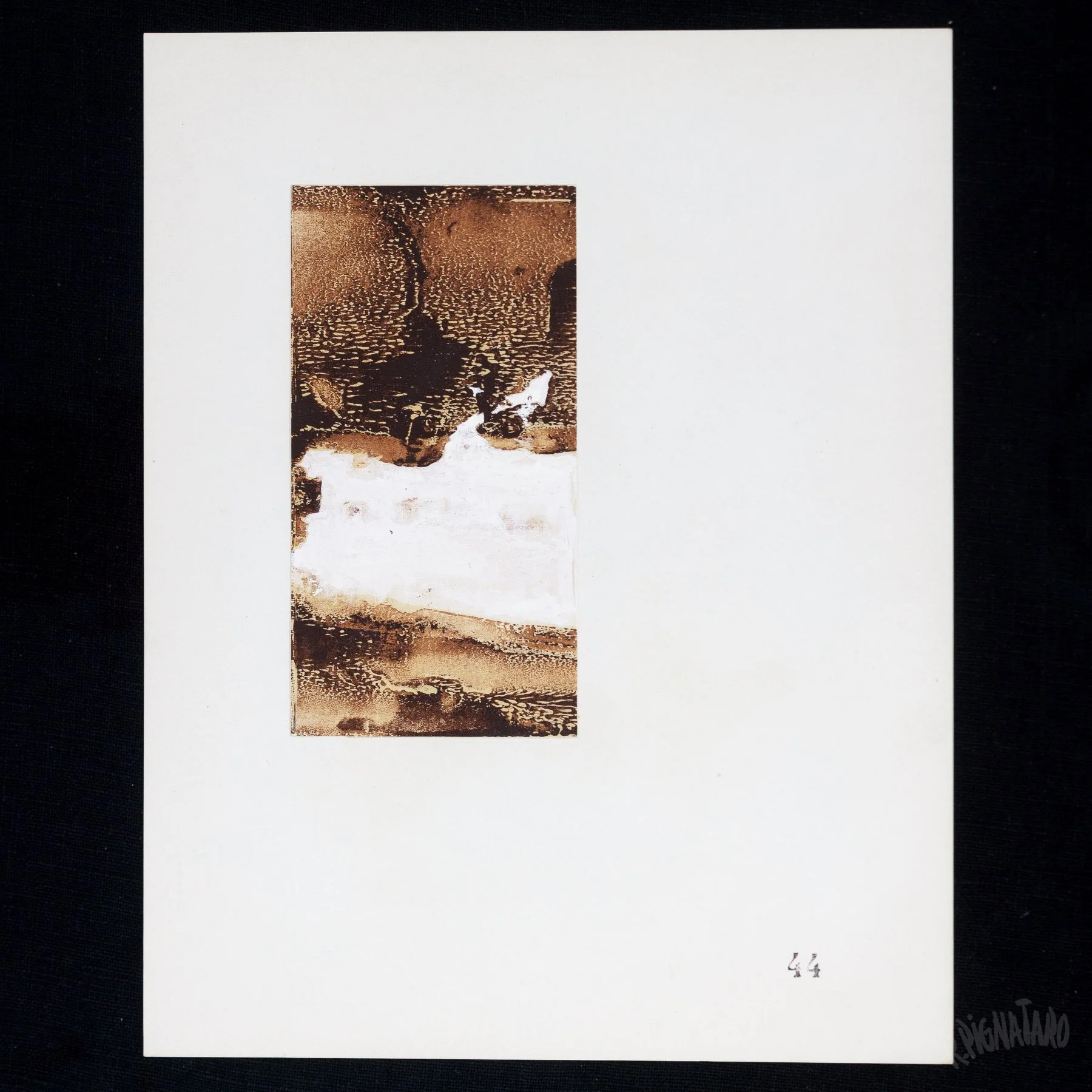

For illustration, the photo gallery below showcases examples of the master artwork. A detail worth noting is that he initially selected 71 small-format abstractions for this project, all unexhibited and all created between 1963 and 1966, but he ultimately narrowed the selection to 30 works that appeared in the book

In the end, he fully embraced the creative challenges posed by black and white printing. He’d always admired the minimalist, yet highly evocative nature of ancient oriental art, such as ink wash painting and East Asian calligraphy. In having to sacrifice color, he saw an opportunity to embody the oriental mindset—the idea that utilizing minimal resources does not necessarily take away from the subject; if done well, it can distill it to its core, revealing it in its most essential form.

The book was printed on Nov 15th, 1968 at ‘Imprenta Fontana’, a now-defunct printing company located in downtown Buenos Aires, just a few blocks from his workplace at the Argentine Central Bank.

Pignataro commissioned a total of 500 copies of ‘A Través de Estampas’, a number reflective of the ambitious nature of this project.

While the printing job was completed successfully, the assembly process took an unexpected turn:

Pignataro had chosen to employ a technique known as “tipped-in plate”. This was fairly common in art books at the time, it entailed printing the artwork images (or plates) separately from the actual book pages, and then gluing them into place in a subsequent process.

However, upon reviewing samples provided by the printer, he found inconsistencies in the placement of the plates. Proper spacing was absolutely crucial to his perfectionist mind; therefore, he found himself unable to entrust them with the tip-in process. Instead, he had them ship all 17,000 book pages and 15,000 plates to his apartment, where he undertook the assembly work himself, dedicating unimaginable hours to this monumental task.

Tipped-in plate in the ‘A Través de Estampas’ book

Considering the first book distribution took place on April 8th, 1969, it should be safe to assume that the assembly process took him approximately 5 months, most likely during weekends and after-work hours.

•••

Book Distribution

I find this phase of the project particularly fascinating. Pignataro’s "door-to-door" strategy for distributing his book not only reflects his driven attitude, the photographs he took to document the process also provide a unique glimpse into the vintage ambiance of many iconic Buenos Aires bookstores of this era, which contribute valuable historical visual context to this story.

Buenos Aires Bookstores

C 1965 - Calle Florida facing south, between Corrientes Ave. and Sarmiento street

According to his personal notes, his bookstore distribution campaign took place between April 8th and May 28th of 1969.

One important aspect that must not be overlooked is that Pignataro's workplace at the Central Bank was located at the heart of downtown Buenos Aires, just a short walk away from the city’s most iconic streets like Florida Street, Lavalle Street and Corrientes Avenue.

These streets were the bustling epicenter of arts and culture in the 1960s, featuring the country's most renowned art galleries, theaters and bookstores, among many other attractions.

This proximity made it very convenient for him to venture out during his lunch breaks or after work, seeking establishments willing to showcase ‘A Través de Estampas.’

As documented by the color slides below, he successfully approached several bookstores, including some notable ones like, ‘Librería El Ateneo’, ‘Librería Editorial del Instituto Di Tella’, ‘Librería Viau’, ‘Librería ABC’, ‘Librería Galatea’ and ‘Librería Editorial Labor’

Outreach

As previously mentioned, not every copy of ‘A Través de Estampas’ was meant for commercial distribution. An important purpose of the book was to serve as a tool for sharing his work within the art community.

Pignataro had engaged in self-promotional efforts before, distributing color slides of his artwork to various personalities, museums, universities, and other art-related institutions in Argentina, the USA, Europe, and Latin America. This approach not only contributed to his local relevance but also, as a South American artist, it was fundamental to establishing and maintaining international awareness of his work.

‘A Través de Estampas’ gave him an opportunity to continue sharing his art globaly, but in a format that would be more personal, enduring and easily accessible than color slides.

Fortunately, he documented many of the initial book recipients, offering insight into his mindset regarding those he entrusted to appreciate his work.

Below, I transcribed of the original list, showing notable book recipients.

It's important to note that while this list reflects recipients Pignataro recorded between the years 1969 and 1972, he likely continued distributing copies of the book well after 1972.

Individual Recipients:

Guillermo Whitelow (ARG)

Jorge Romero Brest (ARG)

Bonnie Tucker (USA/ARG)

Recha Paolini (ARG)

Joseph James Akston (USA)

John Coplans (USA)

Rafael Squirru (ARG)

Elena Perez (ARG)

Aldo Pellegrini (ARG)

Hugo Parpagnoli (ARG)

Paulette Fano (ARG)*

Marta Grinberg (ARG)*

Cesar Magrini (ARG)

Ignacio Pirovano (ARG)

Héctor Basaldúa (ARG)

Pérez Celis (ARG)

Amadeo Dell Acqua (ARG)

Bernardo Graiver (ARG)

Aurelio Macchi (ARG)

Sigwart Blum (GER/ARG)

Samuel Paz (ARG)

Hernández Rosselot (ARG)

*Not on list, based on family account or other sources.

Institutional Recipients:

Diario La Prensa (ARG)

Diario La Nación (ARG)

Diario La Razón (ARG)

Instituto Di Tella (ARG)

Museo del Grabado (USA)

LRA Radio Nacional (ARG)

Argentinisches Tageblatt (GER)

Miami Museum of Modern Art (USA)

Arts Magazine (USA)

Arts Forum Magazine (USA)

Frick Art Reference Library (USA)

Buenos Aires Herald (ARG)

Diario Primera Plana (ARG)

Corrieri Del Itagliani (ITA)

Fundación Franklin de Bibliotecología (ARG)

Museo de Arte Moderno (ARG)

Fondo Nacional de las Artes (ARG)

Diario El Cronista Comercial (ARG)

Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes (ARG)

Centro Argentino Paraguayo de Cooperación Cultural (PAR)

•••

Book Reception

Trying to gauge how ‘A Través de Estampas’ fared with both the art milieu and the broader public has proven particularly challenging, especially considering that this occurred six decades ago within a historical period of Argentine art that suffers from substantial gaps in research.

Some of the obstacles I encountered during my own personal research include:

The original recipients of the book who could provide insights have all passed away.

Argentine media, especially radio and newspapers that might have featured mentions of the book, either provide very limited or no access to online archives and resources.

I don’t live in Buenos Aires, therefore physical access to archives is currently unattainable.

Despite these challenges, I remain optimistic that some insightful conclusions can still be drawn based on Pignataro’s own documentation and personal notes.

Below is a breakdown of the known facts, along with some personal reflections.

Media Mentions (TV & Radio)

There are two recorded instances where ‘A Través de Estampas’ was referenced in Argentine media. A particularly intriguing one is depicted in the photographic slide below. This photo captured the moment when the cover of the book was featured on ‘Universidad del Arte’, a TV show covering matters of arts and culture.

1969. Cover of ‘A Través de Estampas’ being broadcast on Canal 13. Photo taken by Roberto Pignataro.

This was broadcasted somewhere in 1969 on "Canal 13"—one of the four Argentine TV stations in existence at the time. Unfortunately, the specific time and circumstances of this broadcast are unknown.

Transcript of the "Nuestra Vida Artística" show. Provided by Mr. Frejeiro from ‘LRA Radio Nacional’ on July 14th, 1969

The second instance took place on July 12th, 1969 on "LRA Radio Nacional"—a popular Argentine radio station.

There, Amadeo Dell'Acqua and Carlos Arcidíacono, both prominent artists and critics of that era, discussed ‘A Través de Estampas’ during a weekend show titled "Nuestra Vida Artística" (Our Artistic Life).

The document on the right displays a transcript of their dialogue, where Dell'Acqua offered a positive review of the book.

Acquisition by the Buenos Aires MoMA

It is publically documented that the Buenos Aires Museum of Modern Art posses a copy of ‘A Través de Estampas’ in its permanent collection. The specific time and circumstances of this acquisition are unknown.

•••

Book Sales

As of now, I have not found any documented records of book sales. In my research, only a few pieces of information have surfaced, providing limited insight into the book's fate:

500 copies were originally printed

In his later years (mid 2000s), Pignataro still had approximately 100 copies in storage, most of which he unfortunately destroyed before he passed away, only preserving a few copies as evidence of its existence.

Between 1969 and 1972, he recorded 65 copies that were gifted to art-related entities, acquaintances, friends, and family.

One copy has been acquired by the Buenos Aires Museum of Modern Art.

Even when considering this information, over 300 copies still remain unaccounted for. Whether these units were sold, gifted, or disposed of still remains a mystery.

Anecdotally, I have seen copies of ‘A Través de Estampas’ occasionally appear on online marketplaces such as Mercado Libre, AbeBooks, and Amazon. I very recently purchased one from Mercado Libre, mostly out of curiosity, which arrived in surprisingly good shape.

The copy in question was numbered #112, which according to Pignataro’s records, had been personally delivered to Aldo Pellegrini, a celebrated Argentine poet, essayist and art critic who passed away in 1973. It only fascinates me to think about the journey this book has gone through in the last 50 plus years, ultimately finding its way back into my hands. Perhaps delving further into second-hand offerings is where more clues about the book's fate may be uncovered.

•••

Final Conclusions

I will refrain from commenting on specific artistic details of the book, as this aspect is inherently subjective and best left to the discernment of the audience. In my view, the defining innovation of ‘A Través de Estampas’ lies in the concept itself—a wordless book, where the storytelling only unfolds through a game of creative interpretation between the viewer and a series of abstractions.

This artistic proposition represented Pignataro's take on what is perhaps the most significant legacy from the 1960s Argentine art scene—the exploration of novel, more interactive ways to engage audiences with art.

The sociological context from which ‘A Través de Estampas’ emerged makes its story even more captivating. I have marveled earlier at how progressive cultural and economic conditions, combined with the technological advancements of the 1960s, enabled Roberto Pignataro, an average bank employee, not only to autonomously publish an artistic book but also to reach global audiences.

In today's world, it might be hard to grasp how game-changing this was. For most artists in 1960s Argentina the only path to global presence hinged on two critical pillars: the support of patrons like the Di Tella Institute, and the endorsement of influential art critics, such as Jorge Romero Brest and Rafael Squirru.

Pignataro benefited from neither of these support structures; his work did not carry the elements of social commentary and shock-value that so strongly appealed to art critics, patrons and the media. Neither did he project the avant-garde provocateur persona that artists like Marta Minujin, Alberto Greco and León Ferrari enamored the art scene with. On the contrary, his art was introverted, cerebral and canvas-based, existing in a space that was fundamentally at odds with the prevailing spectacle-driven artistic currents of this time like conceptual art, performance art, and happenings.

In the face of these circumstances, he could have either tempered his artistic ambitions or adapted to prevailing artistic trends he didn’t resonate with, in the hope of garnering more attention from the cultural arbiters of the era.

He chose neither. Instead, he astutely capitalized on modern tools and resources available to him at the time—ranging from art supplies, photography equipment, and typewriters to printing services, film development, telephony, and global postmail logistics—and created a ‘mailable’ art form, which allowed him to forge his own pathway to global exposure.

I cannot highlight this enough: you didn’t have to go far back in time to realize how exponentially less accessible these technologies were to the average person in Argentina. 'A Través de Estampas' captures this fascinating moment in time, where cultural, economic, and technological progress intersected to facilitate more democratic opportunities for independent-minded artists like Roberto Pignataro, who were seeking to establish themselves in the art world without compromising their artistic identity.

The question of whether Pignataro’s book ultimately achieved its intended purpose is partially answered by existing documents, yet it is clouded by the absence of more definitive information. Given this reality, I believe the praising words of Amadeo Dell'Acqua and the acquisition by the Buenos Aires Museum of Modern Art should stand out as compelling indicators of its recognition.

That said, the significance of 'A Través de Estampas' should not be measured solely by its artistic impact, but also by the story it tells. Pignataro’s journey in realizing his book uncovers so many fascinating aspects of the art scene and modern life in 1960s Argentina, and does it with a level of nuance and elements of personal experience that broader historical narratives of this period rarely pause to portray.

It is my hope that 'A Través de Estampas' will one day serve not only for the public’s artistic enjoyment but as a valuable historical artifact for art researchers and historians, shedding light on the life of a remarkably creative artist and the fascinating era in which he lived and thrived.